Alfred Crocker Leighton can be considered the grandfather of Alberta art as we know it today. An Englishman drawn to the Canadian west by a sense of adventure, and a commission from the Canadian Pacific Railway, he ended up staying here and made an indelible mark on Alberta’s history of art.

Hired as head of the Art Department at the Provincial Institute of Technology (now SAIT) in 1929, Leighton set out to build a reputable art program. Under Leighton's purview the department flourished—even through the Great Depression when other programs saw declining enrolment and cancellations. In time, the small Art Department at The Tech would become the Alberta College of Art and eventually, Alberta University of the Arts.

In 1933 Leighton established a summer school in the Kananaskis for select art students from The Tech. Within two years, the program had grown so much that it was moved to Banff where it became part of the new Banff School of Fine Arts (today the Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity).

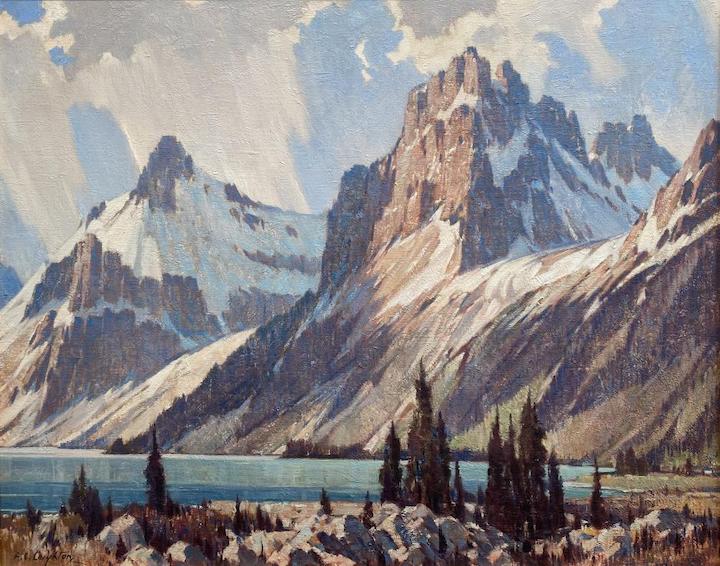

Alfred C. Leighton

Portal Peak & Bow Lake, 1949

oil on canvas, 24" x 30"

Amongst many others, notable students at these summer programs were Marion Mackay (later Nicoll), Margaret Shelton and Bernard Middleton. Middleton was one of Leighton's most promising students, and one of the first students to receive a Fine Arts Certificate from The Tech. In 1937 Middleton was invited to join the staff at the Banff School where he taught classes and managed the art supplies; he left his position four years later, presumably to serve in World War II.

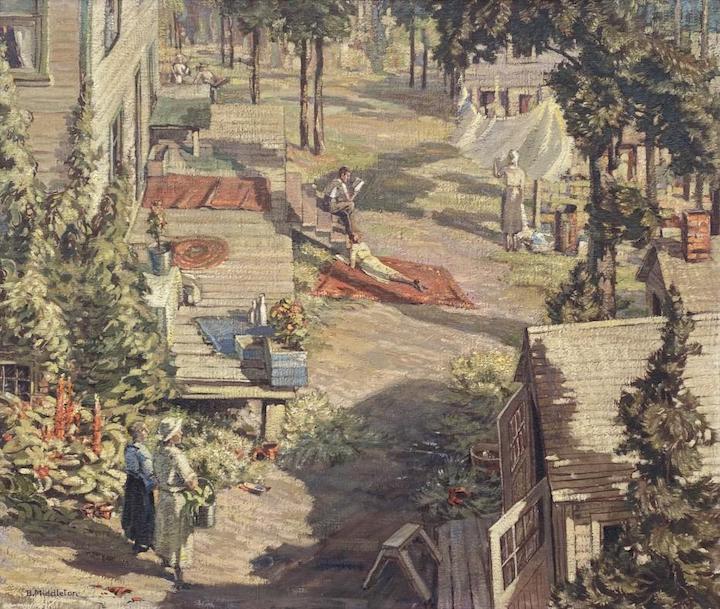

Bernard Middleton

From the Banff School Window, 1938

oil on canvas, 22.5" x 26.5"

Nicholas de Grandmaison who is known best for his pastel portraits of Indigenous people, also taught briefly at The Tech with A.C. Leighton. However, de Grandmaison soon realized that teaching was not for him. He resigned from The Tech to resume his life as a nomad, but this time along with his new wife Sonia. The couple went on the road, travelling from hotel to hotel so de Grandmaison could pursue his artistic practice.

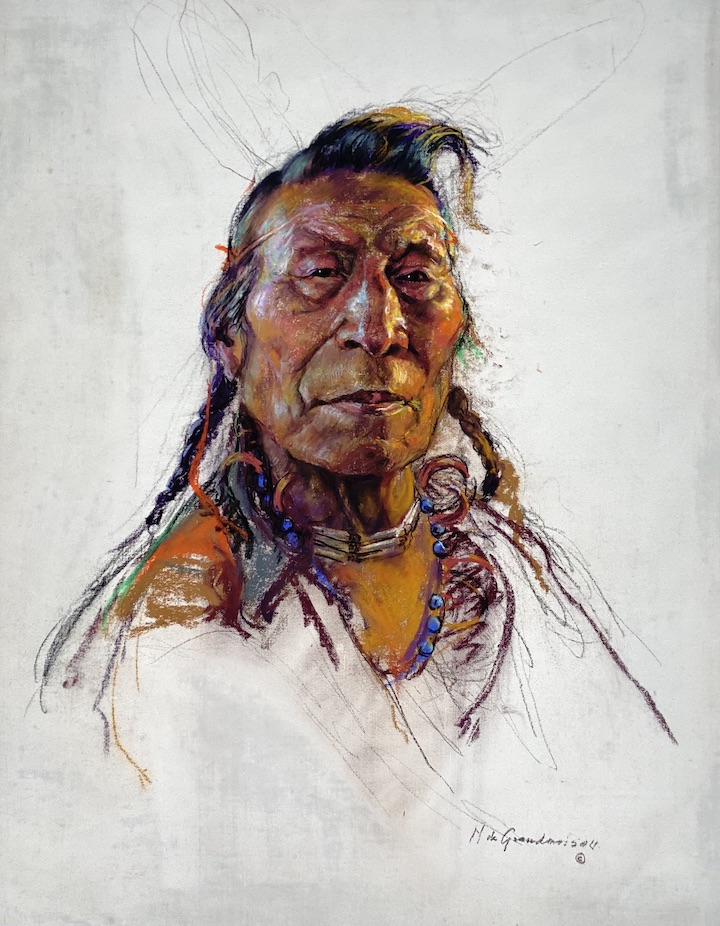

Nicholas de Grandmaison

Good Man, Pahkakino (or Tom Bull) Cree from Hobbema, Alberta, 1954

pastel on canvas, 32" x 24"

Marion Nicoll née Mackay, one of A.C. Leighton's most committed students, graduated with a fine arts degree in 1934. That fall she became the first permanent female instructor at The Tech. She left her position in 1940 when she married Jim Nicoll. Over the next few years the couple moved numerous times due to her husband's job with the Royal Canadian Air Force. When they finally settled again in Calgary, Nicoll was hired to teach during the summers at the Banff School. Here she met fellow instructor, Jock Macdonald who was the new head at The Tech's Art Department; in 1946 she again joined the academic staff there and would teach at the school for the next 20 years. Through the initial academic teachings of Leighton, to her discovery of automatic drawing under the influence of Jock Macdonald in the mid-1940s, Nicoll's work evolved from landscape painting to a distinct style of classical abstraction.

Marion Nicoll

Alberta VI, Prairie, 1960

oil on canvas, 24" x 60"

Henry George Glyde came to Canada in 1935 to teach drawing at The Tech. When A.C. Leighton's poor health forced him into partial retirement in 1936 Glyde, became head of the Art Department. He also joined Leighton during the summer at Banff where he eventually took the lead in 1938; he remained head of the painting department there until 1967. By experimenting with texture and abstraction, over a long career, Glyde created a distinctive reflection of Western Canada based on direct observation and interaction with its landscape and people.

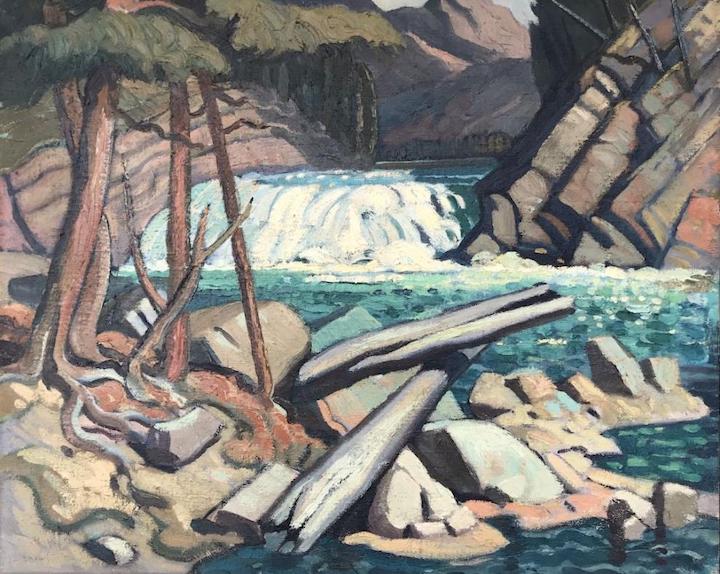

H.G. Glyde

Bow Falls, Banff, circa 1945

oil on canvas, 18" x 22"

Master watercolourist and printmaker, Walter Joseph Phillips reviewed a 1929 Winnipeg exhibition of A.C. Leighton's “I have always felt a genuine admiration for this painter’s superb draughtsmanship, the quality of his colour, and for his handling generally. I have coveted many of his sketches. Now I proudly confess that I own one. It will remain one of my most treasured possessions.” In the same year Phillips and Leighton had a joint exhibition at the Edmonton Museum of Art (now the Art Gallery of Alberta). Perhaps it was inevitable that Phillips would eventually accept a teaching post with Glyde at the Banff School in 1940, and then join the art staff at The Tech in 1941.

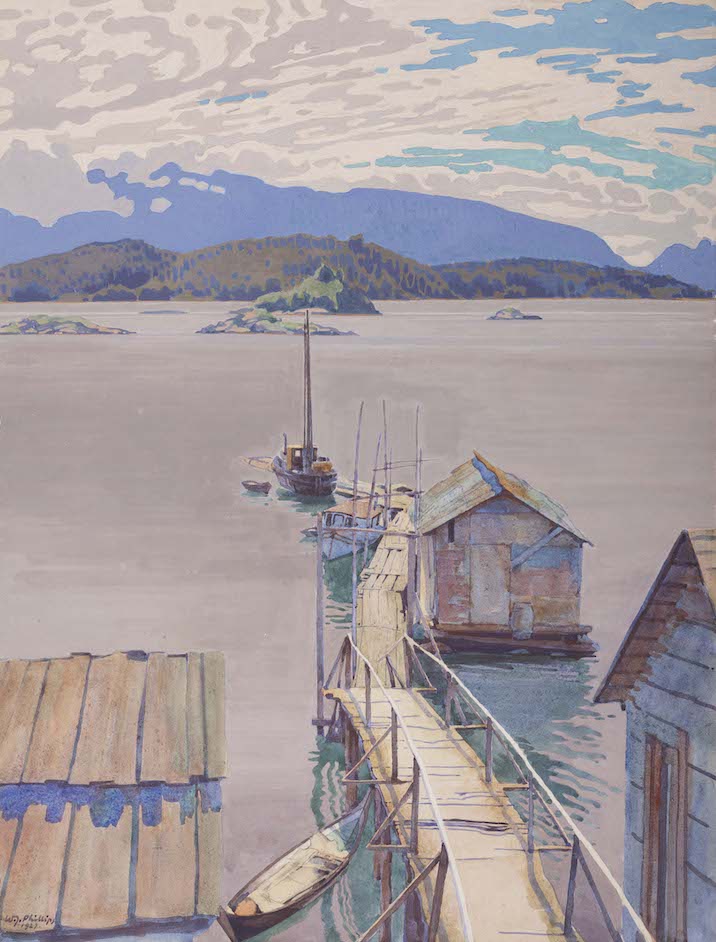

Walter J. Phillips

Floating Dock, Mamalilicoola, B.C., 1927

watercolour on paper, 20.75" x 16"

Luke Lindoe studied in the Art Department at The Tech from 1936 to 1940, and in 1945 became an instructor. In 1950 the school added a course in pottery and ceramics, of which Lindoe was the first instructor in that medium. Like his colleagues above, Lindoe taught in Banff. When the school decided to acquire kilns for the ceramics department, rather than purchasing them Lindoe was hired to teach a "kiln course" wherein he and his students built two kilns.

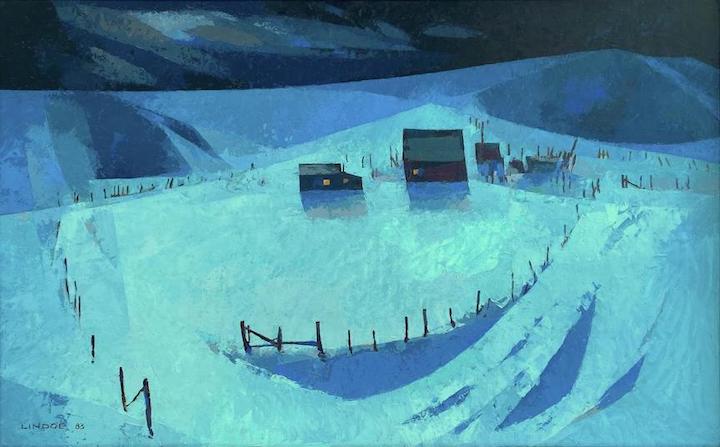

Luke Lindoe

Nocturne from a Train #2, 1983

oil on canvas, 30" x 48"

Best known as a ceramicist, Lindoe was also a skilled painter. He described Nocturne from a Train #2: "This, I feel, is one of my most successful paintings [...] It's a mature, solid painting. This is as good as I get."

Maxwell Bates studied at The Tech briefly under A.C. Leighton’s predecessor, Lars Haukeness. But Bates was a staunch proponent of modernism who thoroughly rejected the traditional academic education provided by The Tech. Bates eventually had his membership with the Calgary Art Club revoked and was prohibited from exhibiting with them.

He soon left Calgary for England where he found commercial success as an artist for several years, until he enlisted in the war. One year in he was captured by the Germans and spent the next five years as a prisoner of war. Upon liberation Bates returned to Calgary via England. Soon thereafter he met fellow modernists Janet Mitchell, Jock Macdonald, Jim and Marion Nicoll, and Luke Lindoe. Together they formed the Calgary Group.

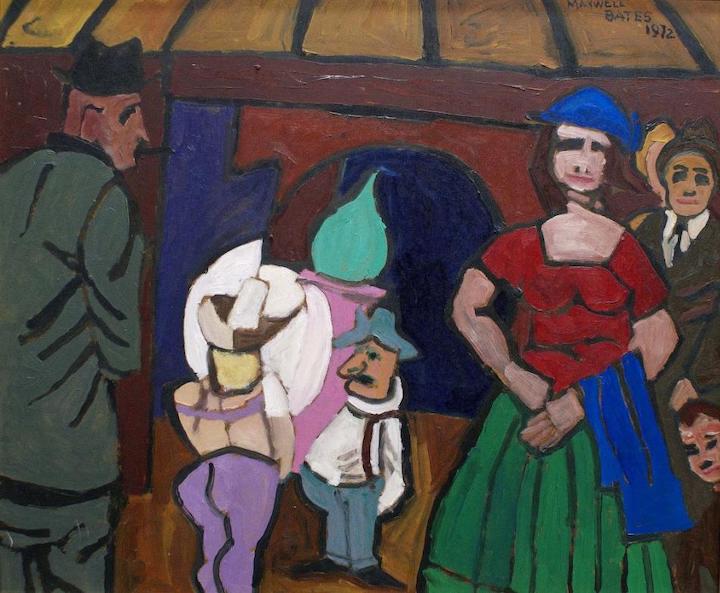

Maxwell Bates

Sideshow, 1972

oil on board, 20" x 24"

Maxwell Bates also worked closely with John Snow. Though a banker by trade, Snow pursued his artistic practice in the evenings. Like Bates he served in the Second World War and was deeply influenced by the modernist art that he saw whilst in Europe.

After the war he studied life drawing at The Tech; here he met and learned from Bates. The men became friends and in 1953 they purchased two decommissioned lithography presses for $15 and made a print studio in Snow's basement. With no one to guide them, they taught themselves how to use it. In addition to pulling hundreds of his own prints on the press, Snow also assisted and collaborated with fellow artists including Bates, W.L. Stevenson and Illingworth Kerr. His home became something of a hub for Calgary artists; Snow provided mentorship, support and a place to gather.

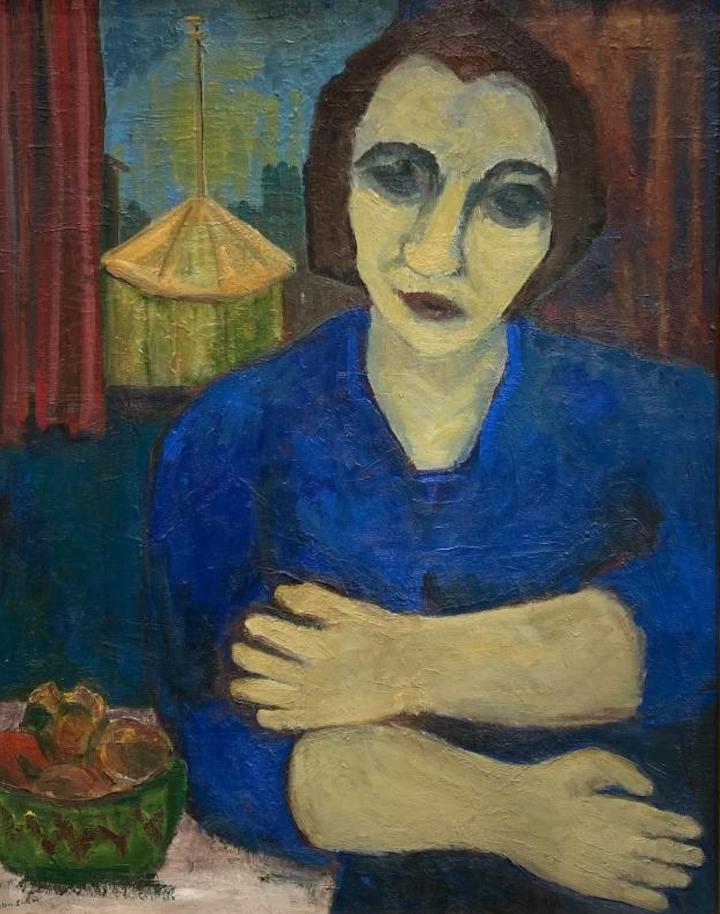

John Snow

Woman in Blue, 1960

oil on board, 30" x 24"

Illingworth "Buck" Kerr came to Calgary in 1947 to assume the role as director of The Tech's Art Department. Under Kerr, the Art Department split from The Tech to become the Alberta College of Art. Though still administrated by The Tech, Kerr believed that the art school's programming would gain the recognition it deserved if given autonomy from the technical college. In the end he was right. The school became an independent college in 1985, and more recently was given status as a university—Alberta University of the Arts.

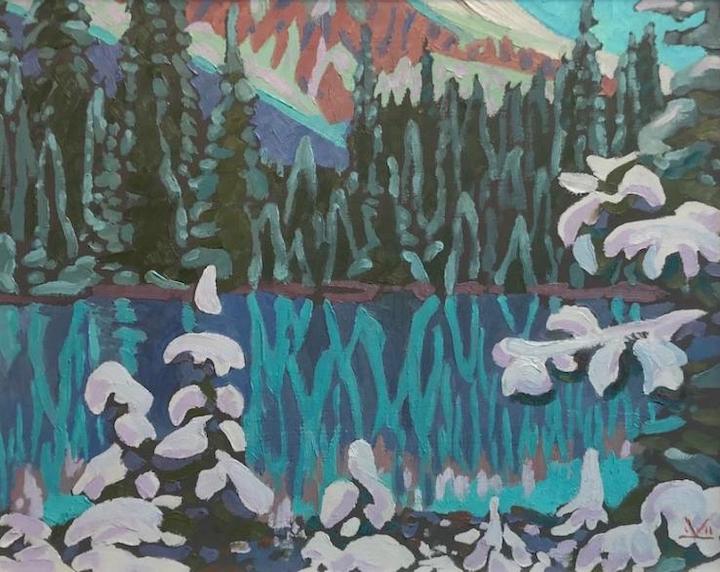

Illingworth Kerr

O'Hara, First Snow, 1982

oil on board, 16.5" x 20.25"

Of Kerr's work, Snow praised "its absolute honesty. It was straightforward and no-nonsense. He had such a fine sense of colour and such a knowledge of prairie landscape. [...] what set him apart most was his ability to look at landscape and think of it in abstract themes of volume, space and colour, [...] without losing the form and contour of the land.”

From A.C. Leighton to Illingworth Kerr, these artists have a shared legacy as teachers and trailblazers who created the artistic landscape of Calgary and Alberta as we know it today.